Squirrel CTF 2025—WriteUp

Today, I’ll be sharing the solutions to the challenges we solved during Squirrel CTF 2025. It was a fun event with a lot of interesting…

Today, I’ll be sharing the solutions to the challenges we solved during Squirrel CTF 2025. It was a fun event with a lot of interesting problems. I’ll show how we approached each one and how we managed to solve them. Let’s get started!

Pwn — dejavu

I was provided with a binary file, I decompiled and this is the content of the win function

Did you spot it? It’s Buffer Overflow in main()

The buffer local_48 is 64 bytes long (as defined by char local_48[64]). However, gets() does not check the size of local_48, so if more than 64 bytes are input, the extra data will overflow into adjacent memory. This adjacent memory includes the saved base pointer (BP) and the return address on the stack.

How to exploit this?

Overflow the buffer: Send more than 64 bytes of input to overwrite the return address on the stack.

Control the return address: Overwrite the return address with the address of the win() function so that when main() returns, it jumps to win() instead of exiting.

Now all we need to do is to find the win address, we will use GDB for this

We will first set a breakpoint in main

Next, we will disassemble win to find its address

As you can see here, the win function starts at address 0x4011f6

The program is 64-bit (x86_64, based on the instructions like endbr64 and 8-byte stack adjustments).

We’ll use this information to craft a precise payload for the buffer overflow exploit. The goal: overflow the 64-byte buffer in main to overwrite the return address with the address of win() (0x4011f6).

Run it and it should give us the flag!

Web — Go Getter

When we visit the site, this is the interface

As you can see here, we are asked to choose an action, either Get GOpher or get the flag, when I choose Get Gopher and submit it, it just show me the picture of Gopher, the mascot of the Golang xd, and when we choose the second option, it gives me an error “Error: Access denied: You are not an admin.”

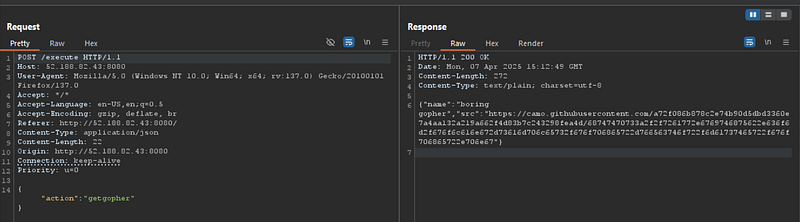

so I launched burpsuite and intercept the request

This is the scripts

app.py

At first, I’ve tried using basic payloads like

Despite all efforts, the result remained the same — permission denied. After hours of solving, a realization struck: what if we resend the payload but adding the action again but capitalize the first letter of the key, changing “action” to “Action”? The idea might seem simple, but it pointed to a deeper issue—a case-sensitivity bug in the server's parser.

What likely happened was that the server’s JSON parser or application logic treated action and Action as completely separate fields. When the request contained “action”: “getflag”, the server correctly checked for proper authorization and denied the request due to insufficient privileges. However, by using “Action”: “getgopher”, the request may have bypassed the security check. This could be because the parser processed Action as a distinct, potentially higher-priority field, or interpreted it as a privileged command. This behavior indicates that the server likely uses a case-sensitive parser, allowing a cleverly crafted request to bypass its intended access controls.

After testing it, it gives me the flag!!! But still weird payload haha

I still have no idea how did I trigger this, it’s on the parser obviously but still unclear. But here’s my understanding behind it

The json.Unmarshal function in Go is generally robust, but it has specific rules:

It matches JSON field names to struct field tags (e.g., “action” maps to Action in the struct via the json:”action” tag).

It ignores unknown fields in the JSON unless you use options like json.Decoder.DisallowUnknownFields().

By default, it silently discards any JSON fields that don’t match the struct tags.

In our payload {“action”:”getflag”,”Action”:”getgopher”}, there are two fields: action (lowercase) and Action (capitalized). The RequestData struct only defines “action” (lowercase), so:

“action”:”getflag” is parsed into requestData.Action.

“Action”:”getgopher” is ignored because there’s no matching struct field tagged with “Action”.

Normally, the Go server should still process “action”:”getflag” and return “Access denied: You are not an admin.” However, the presence of the extra “Action”:”getgopher” field might exploit a parsing quirk or bug:

Unmarshaling Failure: If the JSON contains unexpected fields, json.Unmarshal might fail or behave unpredictably, especially if the struct is strict. However, in this case, it should still succeed (ignoring “Action”). The fact that it didn’t block suggests the parsing logic might have fallen back to a default or forwarded state.

Forwarding Trigger: The switch statement in executeHandler only checks requestData.Action. If the unmarshaling of “action”:”getflag” was somehow disrupted by the extra “Action”:”getgopher” field (e.g., due to a misconfiguration or custom decoder), the server might have skipped the “getflag” case and defaulted to forwarding the request to the Python service. This could happen if:

The Go code uses a custom json.Decoder or middleware that mishandles extra fields.

There’s a logic error where any unrecognized JSON causes the server to forward instead of block.

Flask’s request.get_json() is also robust but flexible. It parses the entire JSON into a Python dictionary, and any extra fields (like “Action”:”getgopher”) are preserved in the data dictionary.

When the Go server forwards our payload {“action”:”getflag”,”Action”:”getgopher”} to the Python service, the Python service sees both fields:

It checks data[‘action’], which is “getflag”, and returns the flag.

The extra “Action”:”getgopher” is ignored because the Python code only cares about the “action” key.

The presence of the word parser suggests that the issue isn’t in the Python service but in how the Go server parses and decides what to do with the JSON. The Python service simply processes whatever it receives, but the Go server’s decision to forward (instead of block) the “getflag” request must stem from a parsing error.

Rev — Droid

I was provided an apk file. The name is droid.apk, I decompile the apk file using Bytecode Viewer (VCB) and upon exploring, I found this MainActivityKt.class and this is the code inside

The provided Java/Kotlin code in MainActivityKt implements a verification system where the check method determines if an input string var0 is valid by ensuring its length matches that of the expected array (31 characters); if so, it XORs each character of the string with corresponding values from the key array to produce a new array var3, then checks if var3 exactly matches the expected array using Arrays.equals. The expected and key arrays contain 31 integers each, representing encrypted or encoded data and the encryption key, respectively, with the goal of finding a string whose XOR with key yields expected, effectively decrypting to retrieve a flag or solution. The method also prints the string representations of var3 and expected for debugging, and provides getter methods to access the expected and key arrays.

To find the flag (the string var0), we can use the expected and key arrays. For each position i in the arrays:

The original character at position i in the flag can be found by XORing the expected[i] with key[i]. This works because if CCC is the original character, EEE is the expected value, and KKK is the key, the encryption process was E=C⊕KE = C \oplus KE=C⊕K. To decrypt, we do C=E⊕KC = E \oplus KC=E⊕K.

Both arrays have 31 elements, so the flag will be a 31-character string.

Calculating the Flag

For each position i from 0 to 30:

Compute the character as flag[i] = (char)(expected[i] ^ key[i]).

This character should be a printable ASCII character (typically between 32 and 126, though spaces and other symbols might also be valid depending on the context).

Let’s perform this computation. We’ll XOR each pair of corresponding elements from expected and key, then convert the result to a character.

Run and it should give the flag

Crypto — Easy RSA

I was provided an easy_rsa.txt containing the given for this challenge

And an easy_rsa.py

Basically, this is an RSA encryption challenge where the primes p and q are generated in a way that makes them close to each other, which is insecure. Here’s how we can crack this:

The key generation shows that:

p is a random prime

q is the next prime after p + random.randint(diff//2, diff)

This means p and q are relatively close to each other

When primes are close together, we can exploit this by:

Taking the square root of n (since n=p*q)

Searching for primes near this value

Here’s the code to get the flag, I use Sagemath Cell Server.

Evaluate and it should give us the flag

Web — EmojiCrypt

I was provided with a script, app.py

The vulnerability is obvious here

Users are auto-registered with a random password

This line generates a 32-digit numeric password using only

0-9.The password is never shown to the user.

Worse, the comment says: “TODO: email the password to the user. oopsies!”

So users are registered with a password they never receive. This is the core flaw.

2. Salt is predictable (made of emojis)

The salt is not user-specific or secret; it just uses emojis in a fixed pattern (joined by aa).

Since salts are stored in the DB, this is not a critical issue on its own, but…

3. No password input required during registration

The password is fully generated server-side.

This means an attacker can register any number of users, and try guessing the generated password.

How to exploit this?

Register a new user — username + email only.

The server silently generates a random 32-digit number password (digits only).

We can assume most of these passwords start with low digits (00, 01, 02, ….)

We can brute-force login with 00000000000000000000000000000000 to 99000000000000000000000000000000.

Here’s the exploit

Run the script to start the bruteforce attack and after some time, it should give us the flag!

Crypto — Secure Vigenere

At first, we can assumea a static ciphertext and try to brute-force or guess the key by testing various combinations derived from “squirrelctf”, right? But it will not work here.

To fully grasp the problem, it’s important to recognize that the challenge goes beyond decrypting one fixed ciphertext. It involves dealing with several encrypted versions (fragments) of the same flag. This is necessary because the ciphertext may differ, or we may need to gather multiple samples to identify a consistent pattern.

Here’s our approach

The server likely returns multiple slightly different encryptions (fragments) of the same flag. Each fragment is encrypted with the same key (“squirrelctf” or its shifts), but there may be variations (e.g., different starting points, padding, or noise).

The plaintext (flag) is constant across all fragments, so we can use this redundancy to our advantage.

Use socket programming to connect to the server. Fetch up to a fixed number of encrypted fragments.

Use regular expressions to extract the ciphertext (e.g., match patterns like “Flag: [a-z]+”) from the server response.

Check the lengths of all collected fragments. Identify the most common length using statistical mode, as fragments of the same length are likely valid encryptions of the same flag.

Keep only the fragments that match this common length to ensure we’re working with consistent data.

The key is squirrelctf. Convert each unique letter in the key to its numerical shift (e.g., s=18, q=16, u=20, etc., where a=0, b=1, …, z=25).

Build a set of all possible shifts from the key’s letters (e.g., {2, 4, 5, 8, 11, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20} for c, e, f, i, l, q, r, s, t, u).

For each position in the fragments, calculate all possible plaintext characters. For a given ciphertext character (e.g., ‘k’ = 10), subtract each shift from the shift set to get potential plaintexts (e.g., (10 — shift) mod 26).

Across all valid fragments, find the intersection of these sets at each position. The intersection gives the only plaintext character that could produce all observed ciphertexts when encrypted with any shift from squirrelctf.

For each position, select the most likely plaintext character (e.g., the only character in the intersection set, or the first if multiple).

Concatenate these characters to form the final plaintext (flag).

Here’s our solution

Run it and it should give us the flag!

Crypto — XOR101

My bike lock has 13 digits, you might have to dig around! 434542034a46505a4c516a6a5e496b5b025b5f6a46760a0c420342506846085b6a035f084b616c5f66685f616b535a035f6641035f6b7b5d765348

The flag format is squ1rrel{inner_flag_contents}. hint: the inner flag contents only include letters, digits, or underscores.

From the description, the key is likely a 13-digit numerical string. It includes all possible patterns that can be XORed, as well as alphanumeric characters or the underscore (“_”). Therefore, the flag is assumed to start with “squ1rrel{“.

Since we know that the string starts from squ1rrel{, all we need to do first is to get our partial key. How?

We will get the first 9 bytes of ciphertext

Then we will get the first 9 bytes of plaintext

XOR to get the partial key

Now that we have the partial key, all we need to do is to do is to try all possible 4-digit endings (0000–9999)

Here’s the solution

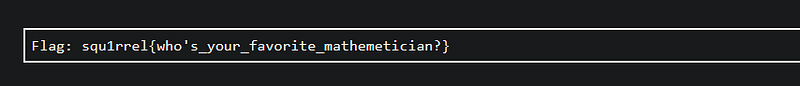

Run the script and upon checking all potential key, this one is the most accurate

Tried to submit it and we’re correct, this is the flag!!!

And that’s a wrap! I hope you all enjoyed reading through my writeup and found it helpful. It was an incredible challenge, and I’m glad to share the experience with you. Out of 541 teams, we managed to secure 41st place, which is a huge achievement considering the competition. While it wasn’t first place, it’s a reflection of the effort and knowledge we put in, and I couldn’t be prouder of how we performed.

Throughout this experience, I learned a ton — whether it was discovering new techniques, sharpening my problem-solving skills, or just pushing through tough moments. It was also a great reminder of how much room there is to grow, and I’m excited for future challenges. This isn’t the end, but rather just another step forward in this journey.

I hope this writeup can serve as a helpful guide for others working on similar challenges, and maybe even inspire someone to take on a competition or problem-solving event. There’s always something to learn, and the process is just as valuable as the result. Thanks to everyone who followed along, and let’s keep improving, supporting each other, and pushing our limits. Here’s to many more victories and experiences to come! Keep grinding, and I’ll see you in the next one!

Last updated